When Sworn Enemies Became Unexpected Allies

The morning of May 5, 1945, dawned with an unusual tableau at Austria’s Castle Itter. On the castle’s ramparts stood a motley crew of defenders — American GIs in olive drab uniforms, Wehrmacht soldiers in field gray, and a collection of French prisoners in whatever attire they could muster. They shared ammunition, swapped battlefield advice, and positioned themselves to repel the imminent assault by Waffen-SS troops surrounding the medieval fortress. Just days after Hitler’s suicide and mere days before Germany’s unconditional surrender, these erstwhile enemies had become brothers-in-arms, united against Nazi fanaticism in what historians would later call “the strangest battle of World War II.”

Inside the castle, former French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud took cover as artillery shells rained down, splintering ancient stonework. Next to him crouched Major Josef “Sepp” Gangl, a decorated Wehrmacht officer who just days earlier had been fighting for the Third Reich. Now, Gangl was risking everything to protect his former enemies. Meanwhile, American Captain Jack Lee directed the defense from near his disabled Sherman tank “Besotten Jenny,” which stood smoking at the castle entrance.

This improbable alliance — Americans, Wehrmacht soldiers, and French political prisoners fighting side-by-side against SS troops — represents one of history’s most remarkable paradoxes: mortal enemies becoming comrades through a shared humanity that transcended the divisions of the most destructive conflict in human history.

A World at War: Context for an Unlikely Alliance

By early May 1945, the Third Reich was in its death throes. Hitler had committed suicide in his Berlin bunker on April 30th. The Red Army had captured Berlin. American and Soviet forces had linked up at the Elbe River. The war in Europe was effectively over, yet pockets of fanatical resistance remained, particularly among SS units who feared prosecution for war crimes and remained loyal to Nazi ideology even as their nation crumbled.

The traditional German Wehrmacht (regular army) and the Nazi Party’s military wing, the Waffen-SS, had long maintained an uneasy relationship. While the Wehrmacht had swallowed the bitter pill of Nazi leadership and fought for Germany, many of its officers came from the traditional military aristocracy and increasingly distanced themselves from Nazi fanaticism as defeat loomed. By spring 1945, with Germany’s defeat inevitable, the split between the professional military and Nazi ideologues widened dramatically.

For the Americans, victory was all but assured. The 12th Armored Division (“Hellcats”) had pushed deep into Bavaria and Austria, accepting surrenders from German units daily. Most American soldiers were simply counting the days until they could go home, avoiding unnecessary risks with the war’s end in sight.

The French VIP prisoners represented yet another faction. Captured by the Germans early in the war or after the fall of Vichy France, these prominent politicians and military leaders had been held as potential bargaining chips by the Reich. They included former Prime Ministers Paul Reynaud and Édouard Daladier, Generals Maxime Weygand and Maurice Gamelin, tennis star and Vichy sports minister Jean Borotra, and Charles de Gaulle’s sister Marie-Agnès Cailliau.

These disparate groups — all enemies according to the formal declarations of war — were about to find common cause in a fight for survival against SS troops determined to execute high-value prisoners before the war’s end.

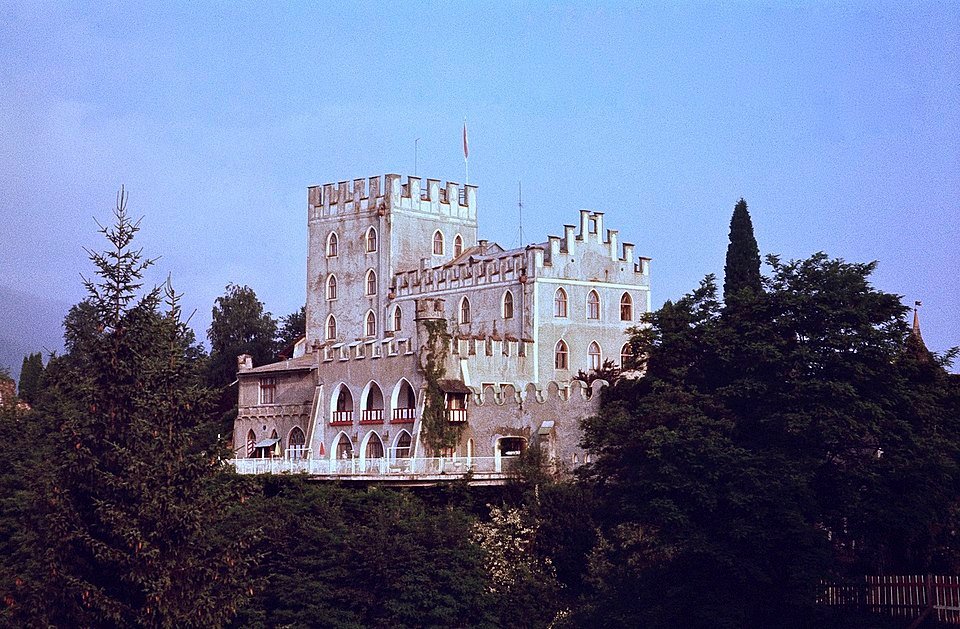

Castle Itter: A Prison for VIPs

Castle Itter stands on a hill near the village of Itter in Austria’s North Tyrol region. Originally built in the Middle Ages and rebuilt in the 19th century, this fairy-tale-like fortress had been leased to the German government in 1940 and incorporated into the Dachau concentration camp system in February 1943, becoming a special prison designated for high-profile detainees the Reich deemed valuable.

Unlike most concentration camps, Itter provided relatively comfortable accommodations for its VIP French prisoners. The former hotel rooms had been converted into cells, but the prisoners received adequate food and could walk within the compound. Nevertheless, as Germany’s defeat became inevitable in early 1945, the prisoners grew increasingly fearful that they might be executed by SS fanatics determined to eliminate witnesses and potential post-war leaders.

The castle’s unusual prisoner population created a peculiar social dynamic. Former political rivals who had once been bitter enemies in French politics now found themselves confined together. Prime Minister Reynaud and General Weygand, for instance, deeply disliked each other, with Reynaud considering Weygand a traitor for his willingness to work with the Vichy regime. These political tensions were so severe that the prisoners required assigned seating during meals to prevent arguments.

Yet as their Nazi captors became increasingly unstable in the war’s final days, these internal French rivalries gave way to a shared concern for survival. The prisoners knew that if fanatical SS units reached them before Allied forces, they would likely be executed.

The Path to Alliance: How Enemies Became Allies

The extraordinary sequence of events leading to the battle began on May 3, 1945. Zvonimir Čučković, a Yugoslav anti-Nazi resistance fighter who worked as a handyman at the castle, left on the pretext of running an errand. His real mission was to contact approaching Allied forces. He traveled toward Innsbruck and eventually made contact with advance elements of the American 103rd Infantry Division.

“In perhaps the only instance in WWII, American GIs, Wehrmacht soldiers, and an SS officer fought side-by-side against Nazi troops—just days before Germany’s surrender.”

The Prison Without Guards

Meanwhile, back at Castle Itter, circumstances changed rapidly. After former Dachau commandant Eduard Weiter died under mysterious circumstances on May 2, the castle’s commander Sebastian Wimmer feared for his own life. He abandoned his post. The SS guards soon followed, leaving the French prisoners effectively in control of the castle. The prisoners armed themselves but feared an attack from SS troops still in the area.

A Second Messenger

When Čučković failed to return, the prisoners sent a second emissary. Czech cook Andreas Krobot bicycled to nearby Wörgl in search of help. There, he encountered Major Josef Gangl, a decorated Wehrmacht officer who commanded the remains of a German unit. Gangl had refused orders to retreat. He had instead aligned himself with the Austrian resistance to protect local residents from SS reprisals.

A German Officer’s Decision

Gangl knew that SS troops were shooting civilians displaying white flags. They were executing men suspected of desertion. To save the prisoners and protect the local population, Gangl made an extraordinary decision. He would seek out American forces and offer his surrender and cooperation.

Americans Enter the Picture

Around the same time, a reconnaissance unit of four Sherman tanks arrived in the area. They were from the American 23rd Tank Battalion, 12th Armored Division, under Lieutenant Jack Lee. When Major Gangl approached under a white flag and explained the situation, Lieutenant Lee immediately recognized the urgency of rescuing the French VIPs.

Formation of the Unlikely Alliance

Lee organized a rescue force. Due to a flimsy bridge that could support only a single tank, he proceeded with just his own Sherman (nicknamed “Besotten Jenny”). He took 14 American soldiers and Gangl’s unit of about 10 Wehrmacht soldiers. This small, mixed force fought through an SS roadblock before reaching Castle Itter on the evening of May 4.

Upon arrival, Lee positioned his tank at the castle’s entrance. He organized the defense with American and German troops working side by side. The French prisoners, rather than hiding as instructed, insisted on joining the fight. They armed themselves with weapons left behind by the fleeing guards.

The Key Figures: Enemies United by Circumstance

Captain Jack Lee

Jack Lee was a 27-year-old officer from Norwich, New York, commanding Company B of the 23rd Tank Battalion. Described as a stocky, imposing figure often with a cigar in his mouth and a .45 caliber pistol in his holster, Lee was a battle-hardened veteran who had led his company through France, into Germany, and finally Austria. Despite being mere days from the war’s end, when most officers would avoid unnecessary risks, Lee volunteered for the dangerous mission to Castle Itter.

Lee’s bravery and leadership during the battle earned him the Distinguished Service Cross, the U.S. Army’s second-highest award for valor. His citation praised his “intrepid actions, personal bravery and zealous devotion to duty.” Later promoted to captain, Lee returned to civilian life after the war and died in 1973.

Major Josef “Sepp” Gangl

Gangl embodied the complexity of German military service during the Nazi era. Born in 1910 in Bavaria, he was a career officer who had fought on both the Eastern and Western Fronts, earning the German Cross in Gold for valor in March 1945. Yet as the war’s end approached, Gangl made the moral choice to protect civilians rather than continue fighting for a lost and immoral cause.

By May 1945, Gangl had connected with the Austrian resistance in Wörgl, providing them with information and weapons. When he learned about the French prisoners at Castle Itter, he saw an opportunity for redemption. His decision to approach the Americans and offer his help represented an extraordinary moral courage.

During the battle, Gangl was killed by a sniper’s bullet while trying to move former French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud out of harm’s way. He was the only defender to die in the battle. After the war, Gangl was honored as an Austrian national hero. A street in Wörgl bears his name, and a memorial plaque commemorates his sacrifice.

The French VIP Prisoners

The castle housed an extraordinary collection of French political and military leaders:

- Paul Reynaud: Prime Minister of France at the start of World War II, who opposed appeasement of Nazi Germany.

- Édouard Daladier: Prime Minister who signed the Munich Agreement but later opposed Germany.

- Generals Maurice Gamelin and Maxime Weygand: Former commanders-in-chief of the French Army.

- Jean Borotra: A champion tennis player known as one of “The Four Musketeers” who dominated tennis in the late 1920s and early 1930s. He later served as Vichy Minister of Sports before falling from favor.

- Marie-Agnès Cailliau: Sister of Charles de Gaulle and an active resistance member.

- François de La Rocque: Leader of the right-wing Croix de Feu movement who later joined the resistance.

- Michel Clemenceau: Son of Georges Clemenceau, France’s World War I leader.

Despite their political differences and personal animosities, these prisoners united in the face of the common threat, with some taking up arms alongside their rescuers.

SS-Hauptsturmführer Kurt-Siegfried Schrader

Adding another layer of complexity to this unusual alliance was Kurt-Siegfried Schrader, an SS officer who had been recovering from wounds at Itter and had befriended some of the French prisoners. When the guards abandoned the castle, the prisoners asked Schrader to help organize their defense. Schrader moved his family into the castle for protection and fought alongside the Americans and Wehrmacht soldiers against his former SS comrades. His presence makes the Battle of Castle Itter the only known instance where an active member of the Waffen-SS fought on the Allied side during World War II.

After the war, Schrader was arrested by American forces for his previous Nazi Party affiliation but received a reduced two-year sentence in recognition of his actions at Castle Itter.

The Battle: A Desperate Stand Against Fanaticism

By the morning of May 5, a force of approximately 100-150 Waffen-SS soldiers had surrounded the castle. They began probing the defenses during the night to assess the strength of the garrison.

Preparing for the Attack

Before the main assault began, Major Gangl telephoned Alois Mayr, the Austrian resistance leader in Wörgl. He requested reinforcements. Only two more Wehrmacht soldiers and a teenage Austrian resistance fighter named Hans Waltl could be spared. They quickly drove to the castle.

The Assault Begins

At dawn on May 5, the SS launched their attack in earnest. The defenders fought from the castle walls and windows. Machine gun fire and anti-aircraft shells battered the ancient fortress. The castle shook so violently that bricks began to collapse.

Loss of Heavy Firepower

Lee’s Sherman tank provided crucial heavy machine gun fire from its position at the main entrance. Then disaster struck. An 88mm anti-tank gun knocked it out of action. With their heaviest weapon disabled and ammunition running low, the situation grew desperate for the defenders.

The Tennis Champion’s Dash

In a particularly dramatic moment, tennis star Jean Borotra volunteered for a dangerous mission. Taking advantage of a lull in the firing, Borotra dressed as an Austrian peasant. He vaulted over the castle wall and sprinted through enemy lines to reach American reinforcements.

Thanks to his athletic prowess, he managed to evade several SS soldiers. He made it to Wörgl, where elements of the 142nd Infantry Regiment were stationed.

Reinforcements Arrive

Borotra asked for an American uniform and guided the relief force back to Castle Itter. The reinforcements arrived around 4 PM, just as the defenders were down to their last rounds of ammunition. The SS forces were quickly defeated, with approximately 100 SS soldiers captured.

The Aftermath: Victory and Historical Significance

The French prisoners were evacuated to France that evening, reaching Paris on May 10. Most would go on to play important roles in post-war French politics and reconstruction efforts. Had they died at Castle Itter, the course of French politics in the post-war era might have been significantly different.

For the Americans and Germans who had fought together, the aftermath was more understated. The seven surviving Americans and the Wehrmacht soldiers piled into a truck for the ride back to Kufstein. There, the German soldiers were sent to POW camps, though most were soon released in recognition of their actions.

Just two days after the battle, on May 7, 1945, Germany signed its unconditional surrender at Allied headquarters in Reims, France. The European theater of World War II was officially over.

The Battle of Castle Itter remains one of the most unusual engagements of World War II. Along with Operation Cowboy (where American forces and German soldiers worked together to rescue Lipizzaner horses), it represents the only known instance where American and German troops fought as allies during the conflict. It is also the only recorded case where an active Waffen-SS officer fought on the Allied side.

The Human Dimension: Finding Common Ground in Crisis

What makes the Battle of Castle Itter truly remarkable is not just its historical uniqueness but the human stories it contains. In the face of death, individuals from opposing sides recognized their common humanity and united toward a shared goal.

“Major Gangl’s final act—sacrificing his life to shield former French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud from sniper fire—stands as one of WWII’s most poignant symbols of redemption.”

Acts of Individual Courage

Major Gangl exemplifies this humanity. A German officer with a distinguished combat record, he chose to protect former enemies at the cost of his own life. His final act—shielding Paul Reynaud from sniper fire—stands as a powerful symbol of redemption.

Similarly, Lieutenant Lee’s willingness to trust former enemies showed remarkable judgment. Rather than viewing all Germans as the enemy, he distinguished between professional soldiers and Nazi ideologues.

Overcoming Differences

Even the French prisoners, despite their political divisions, put aside their differences in the crisis. Former politicians and generals took up weapons alongside American GIs and Wehrmacht soldiers in a common cause.

Moral Choices Under Pressure

The battle illuminates the complex moral choices individuals faced during the war. Nazi Germany was not a monolith. Many Germans, even those in military service, made individual choices to resist when possible. Major Gangl and his men represent the many Germans caught between duty to country and moral conscience, ultimately choosing humanity over ideology.

Reflections: What Castle Itter Teaches Us

The Battle of Castle Itter challenges our understanding of World War II. It reveals the nuanced reality beneath the broad strokes of history. While the conflict is often portrayed as Allied good versus Axis evil, the truth was far more complex. Within Germany itself, divisions between professional military and Nazi zealots created opportunities for unexpected alliances.

Enemies to Allies

The battle demonstrates how quickly former enemies can become allies when facing a common threat. Despite years of combat against each other, American and German soldiers worked together against SS fanaticism. This ability to recognize shared humanity across battle lines speaks to our common bonds even during history’s most divisive conflict.

Individual Moral Choices

Perhaps most importantly, Castle Itter reminds us that war is fought by individuals making moral choices under difficult circumstances. Major Gangl chose to protect civilians and prisoners rather than fight for a lost cause. Captain Lee chose to trust former enemies rather than dismiss their offer of help. The French prisoners chose to fight rather than hide. These individual decisions determined not just the outcome but revealed the character of those involved.

As French prisoner and tennis star Jean Borotra reportedly reflected after the war, “In that moment, we were not French, American, or German. We were just men trying to do the right thing.”

Conclusion: The Legacy of an Improbable Alliance

The Battle of Castle Itter lasted only a day, but its significance resonates far beyond its brief duration. It stands as a powerful reminder that even in the darkest moments of human conflict, our capacity for cooperation, courage, and moral clarity can prevail.

The unlikely alliance of Americans, Wehrmacht soldiers, and French prisoners demonstrates that the lines dividing enemies are often more permeable than we imagine. When faced with true evil—the fanaticism of SS troops willing to execute prisoners as their cause collapsed—former adversaries recognized their common humanity and stood together.

As one of the final engagements of World War II in Europe, the Battle of Castle Itter serves as a fitting coda to the continental conflict. After years of devastation and division, the battle offered a glimpse of reconciliation and cooperation that would eventually allow Europe to rebuild from the ashes of war.

Today, as Castle Itter stands peacefully in the Austrian countryside, few visitors realize the extraordinary drama that unfolded there in the war’s final days. Yet the story of American GIs, Wehrmacht soldiers, and French prisoners standing shoulder-to-shoulder against Nazi fanaticism remains one of history’s most powerful testimonies to the human capacity to transcend division and find common cause in defense of life and dignity.

In a world still plagued by conflict and division, the Battle of Castle Itter reminds us that our common humanity ultimately runs deeper than the ideologies and borders that separate us. Even in the midst of history’s deadliest conflict, enemies could become allies when guided by conscience and a shared recognition of fundamental human values. That lesson, perhaps more than any other, constitutes the true legacy of this strangest of battles.

RECOMMENDED READING

Dive deeper into this historical paradox

Note: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. This means I may receive a commission if you purchase through these links at no additional cost to you.