How Stalin’s regime funded a scientist’s attempt to create human-ape hybrids and rewrite the laws of nature itself

The Proposal That Shocked the World

In September 1925, a letter arrived at the Soviet Department of Scientific Institutions that would become one of the most controversial documents in the history of science. The proposal, written by renowned biologist Ilya Ivanovich Ivanov, was as audacious as it was disturbing: he requested government funding to travel to Africa and create human-ape hybrids through artificial insemination.

The letter’s recipient, Nikolai Gorbunov—Lenin’s former secretary and a powerful figure in Soviet science—was intrigued rather than horrified. Within weeks, the Soviet Academy of Sciences approved Ivanov’s proposal and allocated the equivalent of over one million dollars in today’s currency for what would become known as the “humanzee” project.

Ivanov’s plan was methodical and chilling in its scientific precision. Phase one would involve artificially inseminating female chimpanzees with human sperm in French Guinea. If that failed, phase two would see human women inseminated with chimpanzee sperm at a specially constructed primate facility in the Soviet Union. The goal was to create a new species—part human, part ape—that would serve multiple purposes: proving Darwin’s theory of evolution, striking a blow against religious belief, and potentially creating a new form of super-soldier for the Red Army.

What followed was one of the most ethically disturbing chapters in the history of science, a project so controversial that it remained largely hidden in Soviet archives until the 1990s. When the details finally emerged, Ilya Ivanov earned the nickname “Red Frankenstein,” and his experiments became a symbol of how totalitarian ideology could corrupt scientific inquiry in pursuit of impossible dreams.

The Making of a Mad Scientist

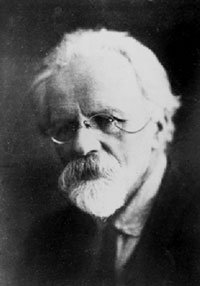

Ilya Ivanovich Ivanov was not a deranged experimenter working in a basement laboratory. Born on August 1, 1870, in the Russian town of Shchigry, he was one of the most respected biologists of his era, a pioneer whose legitimate scientific achievements revolutionized animal breeding and artificial insemination.

Ivanov graduated from Kharkiv University in 1896 and became a professor in 1907. His early work focused on perfecting artificial insemination techniques for horses, achieving remarkable success that had practical applications across the Russian Empire. Using his methods, a single stallion could fertilize up to 500 mares—a dramatic improvement over natural breeding, which allowed a maximum of 30 fertilizations per stallion.

But Ivanov’s true passion lay in interspecific hybridization—the crossbreeding of different animal species. Throughout the early 1900s, he successfully created an array of hybrid animals that seemed to emerge from the pages of mythology: the zeedonk (zebra-donkey hybrid), the zubron (European bison-cow cross), and various combinations of rats, mice, guinea pigs, and rabbits. His laboratory became a menagerie of creatures that nature had never intended to exist.

These early successes gave Ivanov a dangerous confidence in his ability to transcend natural boundaries. If he could cross zebras with horses and bison with cattle, why not attempt the ultimate hybridization—combining humans with their closest evolutionary relatives?

As early as 1910, at the World Congress of Zoologists in Graz, Austria, Ivanov had presented his theory that human-ape hybrids were scientifically possible through artificial insemination. At the time, it was dismissed as theoretical speculation. But the Russian Revolution of 1917 would provide Ivanov with something he had never had before: a government not only willing to fund such research but actively eager to support it.

The Perfect Storm of Ideology and Ambition

The Bolshevik Revolution created a unique historical moment where Ivanov’s radical proposal aligned perfectly with the new regime’s ideological goals. The Soviet leadership, in their campaign to build a new socialist society, were waging war on multiple fronts: against capitalism, against religion, and against the very notion that human nature was fixed and unchangeable.

Soviet ideology embraced the concept of transformation. If the Bolsheviks could revolutionize economics and politics, why not revolutionize humanity itself? The official doctrine spoke of creating the “New Socialist Man”—a transformed human being free from the selfish, competitive instincts that the regime blamed for capitalism and social inequality.

Alexander Etkind, a Cambridge historian who has extensively studied Ivanov’s work, identifies three possible motivations for Soviet support of the project:

Anti-Religious Propaganda: Successful human-ape hybridization would provide devastating evidence for Darwin’s theory of evolution, undermining religious belief and supporting the Bolshevik campaign against the Orthodox Church. As Ivanov himself argued when seeking funding, creating viable human-ape offspring would “prove Darwin right” and “strike a blow against religion.”

The Quest for Super-Soldiers: Some evidence suggests that Soviet military leaders were intrigued by the possibility of creating physically superior beings. Declassified documents revealed claims that Stalin himself had authorized the project, demanding creatures that would be “resilient and resistant to hunger” with “immense strength but with an underdeveloped brain.” Whether these specific quotes are authentic remains debated, but the military applications were obvious.

Scientific Utopianism: The Bolshevik elite included many intellectuals who viewed science as the key to remaking society. Creating new hybrid beings would demonstrate humanity’s power to control its own evolution and transcend natural limitations—the ultimate expression of Soviet technological mastery.

The African Expedition

In March 1926, Ivanov arrived in Paris to prepare for his African expedition. The Pasteur Institute, despite the controversial nature of his research, provided enthusiastic support and access to their primate research station in French Guinea. The institute’s directors were reportedly fascinated by the scientific possibilities, even if they had reservations about the ethical implications.

Ivanov’s first stop in Guinea was disappointing—none of the chimps at the research station were sexually mature enough for his experiments. He spent the summer in Paris, working with the infamous surgeon Serge Voronoff, who was performing his own ethically questionable experiments transplanting ape testicle tissue into aging men as a “rejuvenation therapy.”

The collaboration between Ivanov and Voronoff that summer became a media sensation. Together, they transplanted a woman’s ovary into a female chimpanzee named Nora and then inseminated her with human sperm. While the press waited breathlessly for the results, the experiment failed—but it demonstrated Ivanov’s willingness to push ethical boundaries that other scientists respected.

In November 1926, Ivanov returned to Guinea, this time accompanied by his son, also named Ilya, who would assist in the experiments. Together, father and son supervised the capture of thirteen adult chimpanzees from the interior of the colony, which were brought to the botanical gardens in Conakry and housed in specially constructed cages.

The Experiments Begin

What happened next represents one of the most disturbing episodes in the history of scientific research. On February 28, 1927, Ivanov artificially inseminated two female chimpanzees with human sperm obtained from local volunteers. The identity of the sperm donors remains unknown, though historical accounts suggest Ivanov may have selected African men based on racist theories that they were “more closely related to apes than people of European stock.”

On June 25, 1927, Ivanov inseminated a third chimpanzee with human sperm. The Ivanovs left Africa in July 1927 with their thirteen chimps, already knowing that the first two animals had failed to become pregnant. The third chimpanzee died during the journey to France and was found not to have been pregnant.

The failure of the African experiments did not discourage Ivanov. If anything, it convinced him that the problem lay in the experimental approach rather than the fundamental impossibility of his goal. The remaining ten chimpanzees were shipped to a new primate research center that the Soviet government was constructing in Sukhumi, in the subtropical republic of Abkhazia.

The Sukhumi Horror

The Institute of Experimental Pathology at Sukhumi was designed to be the crown jewel of Soviet primate research, a state-of-the-art facility where the boundaries between species could be systematically eroded in service of ideological goals. Built near Stalin’s birthplace in Georgia, the institute represented the regime’s commitment to transforming science itself.

Upon his return to the Soviet Union in 1927, Ivanov began preparing for the next phase of his experiments—the artificial insemination of human females with chimpanzee sperm. This represented an even more ethically problematic approach, as it involved experimenting directly on human subjects rather than animals.

Through his patron Nikolai Gorbunov, Ivanov gained the support of the Society of Materialist Biologists, a group associated with the Communist Academy. In spring 1929, the Society established a commission to plan the Sukhumi experiments, determining that at least five volunteer women would be needed for the project.

The question of how these women were recruited remains one of the darkest aspects of the entire episode. Some accounts suggest they were found among local prisoners, women who had little choice but to participate in the experiments. The very concept of “voluntary” participation becomes meaningless when applied to subjects under the control of a totalitarian state.

The Project’s Collapse

By 1929, everything was in place for the final phase of Ivanov’s experiments. The Sukhumi facility was operational, human volunteers had been identified, and the Soviet scientific establishment had committed its prestige to the project’s success. But nature and politics conspired to destroy Ivanov’s dreams.

In June 1929, just as the experiments were about to begin, disaster struck. The only sexually mature male ape at Sukhumi—a 26-year-old orangutan named Tarzan—died of a brain hemorrhage. New chimpanzees were ordered from Africa and were expected to arrive in summer 1930, but by then it would be too late.

The late 1920s marked a period of dramatic political upheaval in Soviet science. Stalin was consolidating power and purging intellectuals who had supported earlier Bolshevik leaders. The relatively liberal approach to scientific research that had characterized the early Soviet period was giving way to a more rigid orthodoxy that viewed many experimental programs with suspicion.

Nikolai Gorbunov, Ivanov’s crucial patron, lost his position in the government reshuffling. Without high-level protection, Ivanov found himself vulnerable to criticism from rivals who had long opposed his controversial research. The same ideological flexibility that had initially supported his work now turned against him as the political winds shifted.

The Fall of the Red Frankenstein

On December 13, 1930, the inevitable finally occurred. Ivanov was arrested on charges of counter-revolutionary activity—a catchall accusation that could mean anything from actual political opposition to simply falling out of favor with the regime. He was sentenced to five years of exile in Alma-Ata (now Almaty), Kazakhstan, where he was assigned to work at the Kazakh Veterinary-Zoologist Institute.

The arrest marked the end not just of Ivanov’s career but of the entire human-ape hybridization program. The new shipment of chimpanzees arrived at Sukhumi as scheduled in 1930, but there was no longer anyone authorized to continue the experiments. The animals were redirected to more conventional research purposes.

Ivanov spent his final years in exile, his health deteriorating under the harsh conditions of Soviet punishment. On March 20, 1932—ironically, the fifteenth anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution that had made his experiments possible—he died of a stroke while waiting for a train to Moscow. He was 61 years old.

The renowned physiologist Ivan Pavlov wrote Ivanov’s obituary, published in 1933 in the journal Nature. Notably, Pavlov mentioned the human-ape hybridization experiments in only a single sentence, treating them as a minor footnote to Ivanov’s legitimate scientific achievements. The Soviet scientific establishment was already working to erase the memory of its most embarrassing episode.

The Cover-Up and Revelation

For more than half a century, the full details of Ivanov’s experiments remained buried in Soviet archives. The government had every reason to suppress the story—it reflected poorly on Soviet scientific judgment and raised uncomfortable questions about the regime’s willingness to support ethically dubious research.

During the Cold War, occasional rumors about “Stalin’s ape-man experiments” circulated in the West, but they were generally dismissed as anti-Soviet propaganda. The scientific community preferred to focus on Ivanov’s legitimate contributions to animal breeding rather than his more controversial work.

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 finally opened the archives that contained the full documentation of Ivanov’s project. Historians like Alexander Etkind and Kirill Rossiianov began piecing together the complete story from thousands of pages of previously classified documents, correspondence, and research notes.

When the details were finally published in the 1990s and 2000s, they shocked the scientific community and the general public. The scope and systematic nature of the experiments was far more extensive than anyone had imagined. Here was not a lone mad scientist working in isolation, but a major government-funded program that had commanded significant resources and official support.

The Scientific Reality Check

Modern genetics has vindicated the fundamental impossibility of Ivanov’s goals. While humans and chimpanzees share approximately 98.8% of their DNA, the differences are concentrated in crucial areas that make hybridization impossible.

Humans have 46 chromosomes while chimpanzees have 48, meaning that their chromosomes cannot pair properly during reproduction. Even if fertilization were to occur, the resulting embryo would be unable to develop properly. Additionally, an estimated 40 million base pair differences exist between human and chimpanzee genomes—variations that create insurmountable biological barriers to crossbreeding.

The ethical problems with Ivanov’s work are even more obvious today than they were in the 1920s. The experiments violated every principle of informed consent, subjected both animals and humans to unnecessary suffering, and reflected the racist assumptions about human hierarchy that were common in his era.

Yet Ivanov’s work also reveals important insights about the relationship between science and politics. His experiments were not the product of individual madness but of a systematic ideological commitment to transcending natural limitations. The Soviet state’s support for his work reflected a broader utopian vision that viewed science as a tool for remaking humanity itself.

Cultural Legacy and Modern Echoes

The story of Ivanov’s experiments has left a lasting mark on Russian culture. Mikhail Bulgakov’s satirical novel “Heart of a Dog,” considered a masterpiece of Russian literature, features a character clearly inspired by Ivanov—Professor Preobrazhensky, who accidentally transforms a stray dog into a human being.

In 1932, the composer Dmitri Shostakovich began work on an opera called “Orango,” which told the story of a half-human, half-ape creature created by a French scientist. The opera was never completed, possibly because the subject matter had become too politically sensitive, but the surviving fragments were discovered in 2004 and subsequently performed.

The “humanzee” concept has also found new life in contemporary discussions about genetic engineering and synthetic biology. While the specific goals of Ivanov’s experiments remain impossible, modern science has achieved things that would have seemed equally fantastic to 1920s researchers—creating genetically modified organisms, cloning mammals, and even developing human-animal chimeras for medical research.

Lessons from the Laboratory of Horrors

The Ivanov experiments serve as a crucial cautionary tale about the dangers of politicized science. When scientific research becomes subordinated to ideological goals, the results can be both scientifically worthless and ethically catastrophic.

Several key lessons emerge from this dark chapter:

The Corruption of Scientific Method: Ivanov’s experiments were designed not to test genuine scientific hypotheses but to confirm predetermined ideological conclusions. This represents a fundamental corruption of the scientific method, where evidence is sought to support beliefs rather than to challenge them.

The Vulnerability of Scientists: Ivanov’s fate illustrates how scientists can become victims of the same political forces they initially sought to serve. His enthusiasm for the regime’s anti-religious agenda ultimately provided no protection when the political winds shifted.

The Importance of Ethical Oversight: The complete absence of ethical review in Ivanov’s work demonstrates why scientific research requires independent oversight. Without external checks on research practices, even respected scientists can pursue projects that violate basic human dignity.

The Danger of Utopian Thinking: The Soviet support for Ivanov’s experiments reflected a broader utopian belief that science could be used to create a perfect society. Such thinking can lead to the dehumanization of research subjects and the abandonment of ethical constraints.

The Specter of Renewed Interest

While Ivanov’s specific goals remain scientifically impossible, the underlying questions he raised about human enhancement and genetic modification have gained new relevance in the 21st century. Modern biotechnology has achieved remarkable feats—creating genetically modified organisms, developing gene therapies, and even beginning to edit human genetic code.

In 2019, researchers actually created viable human-monkey embryos in laboratory settings, though they were destroyed after 14 days and were intended for medical research rather than reproductive purposes. While this work operates under strict ethical guidelines that Ivanov never considered, it demonstrates that the boundary between species is not as absolute as once believed.

The persistence of interest in human enhancement—whether through genetic engineering, artificial intelligence augmentation, or other means—suggests that the utopian impulses that drove Ivanov’s work have not disappeared. The challenge for contemporary science is to pursue legitimate research goals while maintaining the ethical constraints that Ivanov’s era lacked.

The Verdict of History

Today, Ilya Ivanov is remembered primarily as a cautionary figure—a brilliant scientist whose legitimate achievements were overshadowed by his participation in one of the most ethically problematic research programs in modern history. His work on artificial insemination and animal breeding remains scientifically valuable, but his human-ape hybridization experiments stand as a monument to the dangers of unchecked scientific ambition.

The “Red Frankenstein” represents something more troubling than individual madness or scientific error. Ivanov’s experiments were the product of a systematic attempt to use science as a tool of ideological transformation, an effort to remake humanity itself in service of political goals.

The fact that such a program could gain official support, command significant resources, and operate for several years without meaningful oversight reveals how quickly scientific research can become corrupted when it serves political rather than scientific purposes.

Perhaps most disturbing of all, Ivanov’s experiments demonstrate how easily the fundamental ethical principles that should govern scientific research can be abandoned when researchers become convinced that their work serves a higher cause. The road from legitimate scientific inquiry to monstrous experimentation can be shorter than we might imagine.

The Enduring Warning

As we stand on the threshold of unprecedented advances in genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology, the story of Ilya Ivanov’s human-ape hybridization experiments offers crucial warnings for the future. The same technological capabilities that promise to cure diseases and enhance human life could also be used to pursue goals that violate human dignity and scientific ethics.

The Soviet Union’s support for Ivanov’s work reminds us that even apparently progressive political movements can embrace scientifically and ethically dubious research when it serves their ideological purposes. The enthusiasm of the international scientific community for some aspects of Ivanov’s work demonstrates that scientific prestige provides no guarantee of ethical judgment.

Most importantly, Ivanov’s story illustrates that the most dangerous scientific research may not come from isolated mad scientists working in secrecy, but from respected researchers operating with official support and convinced that their work serves the greater good.

The true horror of the “Red Frankenstein” lies not in the specific experiments he conducted, but in the system of thought that made those experiments seem not only possible but desirable. As long as we remember that lesson, perhaps the victims of Ivanov’s research—both human and animal—will not have suffered entirely in vain.

In the end, Ilya Ivanov achieved a form of immortality, though not the kind he sought. He will be remembered not as the creator of a new species, but as a symbol of science gone wrong—a reminder that the pursuit of knowledge without wisdom, and power without conscience, leads inevitably to the corruption of both science and humanity itself.

FURTHER READING: The Dark Science of Soviet Experiments

For readers interested in exploring the disturbing intersection of science and ideology in Soviet history, these scholarly works provide comprehensive analysis of Ivanov’s experiments and their broader context:

Note: As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. This means I may receive a commission if you purchase through these links at no additional cost to you. Please verify all links and image sources.